Gratian, Concordia discordantium canonum

| Title | Gratian, Concordia discordantium canonum |

|---|---|

| Key | GR |

| Alternative title | Decretum Gratiani |

| Wikidata Item no. | Q1182119 |

| Size | Very large (more than 2000 canons) |

| Terminus post quem | 1139 |

| Terminus ante quem | 1150 |

| Century | saec. XII |

| Place of origin | Bologna |

| European region of origin | Northern Italy |

| Author | Anders Winroth |

| No. of manuscripts | very many (100+) |

Gratian was a teacher of canon law in Bologna around 1140. He compiled his own textbook which he called Concordia discordantium canonum ("Harmony from Discordant Canons"), thus signaling his intention to reconcile systematically contradictory statements of ecclesiastical law. The work soon became know as the Decreta for short but is in modern times usually referred to as the Decretum.

Gratian's Biography

Only three facts are known with certainty about Gratian's life:

- Gratian compiled some version of the Decretum.

- Gratian was one among three legal experts who advised the cardinal legate Goizo when he decided a legal case in Venice in 1143.

- Gratian died as bishop of Chiusi on the 10 August in an unknown year.

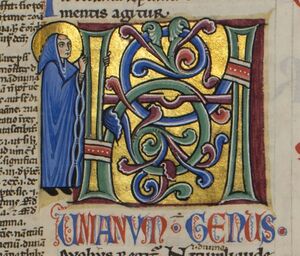

The earliest teachers of canon law in Bologna seem to have known little about Gratian. Paucapalea, for example, never even mentions him by name, only as "the master/magister who put together this work (i.e., the Decretum)" (magistri autem hoc opus condentis). Parisian masters believe they knew more, but their claims are contradictory. A very early gloss (possibly formulated before 1150) in the manuscript Pf states that Gratian was a bishop. The abbot of Mont St. Michel, Robert of Torigni, reported in his chronicle that Gratian was bishop of Chiusi. That report is confirmed by the necrology of the cathedral chapter of Siena, who remembered the death of Bishop Gratian of Chiusi on 10 August each year. A miniature in a Saint-Omer manuscript depicts Gratian teaching in his school in an episcopal mitre (see image below).

Other close contemporaries in Paris and elsewhere instead claimed that Gratian was a monk. Notable among them is the author of the Summa Parisiensis (composed in Sens in 1167 or 1168), who said so repeatedly. The glossator known as "Cardinalis" (Raymondus de Harenis, died 1176 or 1177) also stated that Gratian was a monk. He has over time been placed in several different monasteries, first by the Roman law teacher Odofredus (died 1265) in the Monastery of Saints Felice and Nabor in Bologna.

The tradition that Gratian was a monk was very strong in the late twelfth century and grew even stronger later. Very many manuscript illuminations depict Gratian as a monk (Murano 2025). The idea that Gratian was a monk specifically in the Monastery of Saints Felice and Nabor in Bologna was widely spread in the twentieth century by being included in the very influential Prolegomena of Alphonse Van Hove (1928, 1945). It reappeared in practically every treatment of Gratian's biography after that date, until John Noonan demonstrated the late origins of this claim in the writings of Odofredus.

Current scholarship is divided on how to interpret these several pieces of information. Some state that the claim that Gratian was a monk was so widely spread already in the twelfth century that it must reflect a living tradition, while others see that tradition as having been created to make up for early Bolognese masters actually not knowing anything about Gratian. Most scholars agree, however, that Gratian became the bishop of Chiusi.

Gratian's Decretum

The Decretum was produced in a two-stage process, with Gratian himself finishing a first recension at some point probably soon after 1139, before being made Bishop of Chiusi in Tuscany, where he appears to have died on 10 August, c. 1145. This first recension contained 1860 canons which Gratian discussed in almost 1000 discursive comments (“dicta”) of varying length. He began by discussing the characteristics of law and then clerical office and life in a long treatise as yet without subdivisions. He divided the rest of the Decretum into 36 causae (“cases”), each of which describes an imagined situation from which Gratian derived and discussed up to eleven legal questions. The first causa is devoted to simony, the sin of selling ecclesiastical office. Causae 2-8 concern legal procedure, while later causae treat ecclesiastical property and tithes, monastic law, oaths, just war, and heresy. The last quarter of his work, causae 27-36 makes up a substantial treatise on marriage law, into which Gratian inserted, as causa 33, quaestio 3, a long and innovative treatise on penance.

We might imagine that Gratian left teaching abruptly, never finishing and polishing his collection. His successors thought the work was incomplete, so they added some 2000 further chapters to it, drawn mainly from the same sources as Gratian had used for the first recension. Their additions are distributed across the entire Decretum and include rather few dicta, often making the second recension appear a less tightly argued work than the first. Somewhat later, they added the third part of the Decretum, known as de consecratione, a collection of canons (but no dicta) concerning such sacramental law (baptism, confirmation, consecration of church buildings and objects) as Gratian had not treated in the first recension.

The text of the Decretum was subject to even more editorial work over several decades after the completion of the second recension. When the second recension became known, owners and users of existing first-recension manuscripts often updated them to the second recension by adding the next texts on available space in the margins, or they added more parchment. That process is directly visible in the manuscripts Bc Fd Vx and indirectly in Aa.

When such updated first-recension manuscripts were used as exemplars in copying, the resulting copy may be characterized as containing a "mixed recension", with some parts reflecting the first recension and some the second. This explains the very great variety in the texts appearing in twelfth-century manuscripts. The phenomenon disturbed teachers and students of canon law and efforts were expended to ameliorate the situation. Teachers made a habit of reading out aloud the text of their own manuscript when they were lecturing, ensuring uniformity of the text in the classroom. One or several persons in Paris produced a slightly revised version of the text of the Decretum in the 1160s. which modern scholars label the Σ (sigma) recension. Similarly, another revised version was produced in Bologna in around 1180, labelled the Π recension.

Some two hundred chapters were added, often drawing on Burchard's Liber decretorum, which had not been used for either the first or the second recension. Many of these additions first appear in manuscripts of the Π recension. They were already in the twelfth century called paleae ('chaff', in distinction from the grain of the rest of the work). In some cases editorial work cancelled canons that were duplicated or otherwise less desirable. The cancelled canons are, confusingly, also called paleae, although some modern scholars refer to them as duplicates instead.

Gratian in the Clavis canonum Database

Gratian's Decretum (GR) was added to the database in 2021. It is based on Friedberg's edition. Hopefully, a modern edition of the first recension will be included in the future.

Manuscripts and Editions

Manuscripts

For manuscripts, see Category:Manuscript of GR (508 entries) and the List of Gratian Manuscripts for more details (including fragments, lost manuscripts, and erroneous references).

Complete Editions

For early editions, see the bibliographies by Will and Adversi. The Decretum was very often printed, typically including some form of the Glossa ordinaria, between 1471 and 1616.

- Gratian's work was first printed by Heinrich Eggestein of Strasbourg in 1471 (Copy of Bodleian Library, Oxford, vol. 1 and 2, available online). The edition also contains the Glossa ordinaria, in what is probably the printed version that is most faithful to the medieval tradition. Later editions, especially after 1500, contain often radically edited versions.

- The official Roman edition of 1582 is available from UCLA, with a useful clickable table of contents. The editio Romana also contains the Glossa ordinaria in a version that has been much revised in comparison with the medieval tradition.

- The most recent complete edition of the second recension of Gratian's text is the one that Emil Friedberg published 1879 in Leipzig and available online here (and elsewhere). The Munich digital copy is usefully equipped with a table of contents, page images, and text. The Clavis database entries link to this digital version, too.

- The working edition of the first recension, produced by Anders Winroth, is available online. You will also find useful materials here, e.g. an overview over the manuscripts.

Partial Editions

Several scholars have in recent decades published new editions of sections of the Decretum:

- Titus Lenherr, Die Exkommunikations- und Depositionsgewalt der Häretiker bei Gratian und den Dekretisten bis zur Glossa ordinaria des Johannes Teutonicus, Münchener theologische Studien, III. Kanonistische Abteilund 42 (St. Ottilien: Eos, 1987), 18-56. C.24 q.1.

- Regula Gujer, Concordia discordantium codicum manuscriptorum? Die Textentwicklung von 18 Handschriften anhand der D.16 des Decretum Gratiani, Forschungen zur kirchlichen Rechtsgeschichte und zum Kirchenrecht 23 (Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau, 2004), 392-415. D.16.

- Enrique De León, La "cognatio spiritualis" según Graciano, Pontificio Ataneo della Santa Croce: Monografie giuridiche 11 (Rome, Giuffré, 1996), 138-168. C.30, qq.1, 3, and 4.

- Atria Larson, Gratian's Tractatus de penitentia: A New Latin Edition with English Translation, Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Canon Law 14 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2016), 2-279. C.33 q.3 De penitentia. Includes an English translation.

- Jean Werckmeister, Décret de Gratien, causes 27 à 36: Le mariage; Édition, traduction, introduction et notes, Source canoniques 3 (Paris: Cerf, 2011), 78-699. C.27-C.36, except de penitentia (C.33 q.3). Includes a French translation.

Literature

Aldo Adversi, "Saggio di un Catalogo delle edizioni del 'Decretum Gratiani' posteriori al secolo XV." Studia Gratiana 6 (Bologna, 1959), pp. 281-451.

Jürgen Buchner, Die Paleae im Dekret Gratians: Untersuchung ihrer Echtheit, Pontificium Athenaeum Antonianum , Facultas Iuris Canonici 127, (Rome, 2000).

Atria Larson, Master of Penance: Gratian and the Development of Penitential Thought and Law in the Twelfth Century, Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Canon Law 11 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2014).

Giovanna Murano, "Graziano e il Decretum nel secolo XII," Rivista internazionale di Diritto Comune 26 (2018), p. 61-139.

Giovanna Murano, "The Life and Iconography of Gratian: A 'Mise au point' (Part I)," Saeculum Christianum 32:1 (2025), p. 30-42. https://doi.org/10.21697/sc.2025.32.1.3

Giovanna Murano, "The Life and Iconography of Gratian: A 'Mise au point' (Part II)," Saeculum Christianum 32:2 (2025), p. 5-19. https://doi.org/10.21697/sc.2025.32.2.1

John T. Noonan Jr., "Gratian Slept Here: The Changing Identity of the Father of the Systematic Study of Canon Law," Traditio 35 (1979), p. 145-172.

John Wei, Gratian the Theologian, Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Canon Law 13 (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2016).

Rudolf Weigand, Die Glossen zum Dekret Gratians: Studien zu den frühen Glossen und Glossenkompositionen, Studia Gratiana 25-26 (Rome, 1991).

Erich Will, "Decreti Gratiani incunabula: Beschreibendes Gesamtverzeichnis der Wiegendrucke des Gratianischen Dekretes" Studia Gratiana 6 (Bologna, 1959), p. 1-280.

Anders Winroth, The Making of Gratian's Decretum (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Anders Winroth, "Where Gratian Slept: The Life and Death of the Father of Canon Law," Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung 99 (2013), p. 105–128.